I competed in the inaugural Ironman 70.3 Miami half-Iron distance triathlon on October 30, 2010 in downtown Miami, Florida. This race would be my second WTC/Ironman event of the four half- and full-Iron distance events I’ve raced in the past two years.

The race was plagued with problems starting well before race day and certainly at every facet of the event itself.

Rather than write a typical race report that describes my day from start to end of the race, I’m going to include a little more detail (prior to race day, for example) to illustrate how poorly managed this event actually was.

In all fairness, it is worth noting that WTC has recently issued an apology to athletes who competed in Miami and also offered a complimentary entry to an Ironman 70.3 event in 2011, which is an appropriate gesture given the loss (time, training, financial) the athletes and their families suffered in Miami at this event.

Event Communications

In the weeks leading up to Ironman 70.3 Miami, several emails were disseminated by race management to alert athletes to course changes, rules announcements, wave start times, etc. Apparently any athlete who unsubscribed from the “newsletters” that were being distributed in early 2010 (consisting of sponsor announcements, advertisements, and professional athlete commitments) was also removed from critical race information distribution.

Course changes were made to all three courses with most dramatic being on the run course. The original event included an out-and-back run course that went along Biscayne Bay and over the MacArthur Causeway but was changed in the last couple weeks before the event to include a smaller double out-and-back course that went over Biscayne Bay to Dodge Island and back before turning around, resulting in eight climbs of the bridge. This change is significant in that athletes must sign up a year in advance for many Ironman events (due to how quickly they sell out, as this event did in less than two months) and the decision to register is made on things such as course layout. While it’s entirely understandable that course changes will occur from time to time, there’s no excuse to run athletes over a bridge eight times, especially when they’ve already committed to a race under such different expectations.

As recently as the week of the event, the website still had questions in its FAQ section that listed “Details coming soon” as the answer. Rules were posted during the week prior to race day that included rules not typically expected in such an event. For example, an athlete with his or her wetsuit pulled lower than the waist and not inside a changing tent would receive a 4:00 penalty to be served in a penalty box. Other rules, such as race management’s prohibition of items other than bike and helmet at the bike rack (all changing of shoes, etc. must be conducted in the changing tent and transition bags removed by volunteers) were communicated which undoubtedly shape the way athletes pack for the event.

Information in the emails conflicted with information on the website, even in cases where the email referred to the website itself for further information. For example, the maximum temperatures for wetsuits were listed as 76F and 84F (for athletes who did or did not wish to remain eligible for age group awards or Championship slots) on the website, whereas some emails referred to the new WTC wetsuit temperatures of 76.1F and 83.8F.

Packet Pick-up, Expo and Bike Check-in

We drove to Miami on Thursday before the race; arriving in the afternoon around the time that packet pick-up was closing, so we decided to go the following morning. When we went to the packet pick-up location around 10:00, we found a line that extended to the expo entrance. I left my wife in line and checked to make sure this was leading to the check-in stations, which it appeared to be. We later realized that there was no line for check-in and that everyone was standing in the USAT Registration line, with the check-in folks taking people who finished USAT registration (many of the athletes were from outside the US so they needed a one-day membership) as they completed the process. We could have waited five minutes, but stood in line for about 45 minutes since there was no signage or volunteers telling people they could bypass the USAT station.

Upon getting my packet, I opened it up to confirm that everything that should be in it was in fact there. I noticed there was no event shirt (which I’m used to seeing) and was told that we get a shirt if we finish the event. A beer company representative was handing out cheap hats with the event logo nearby, and by cheap, I mean that they had cardboard-filled brims rather than the lightweight plastic-filled brim that is common today in sports caps. To summarize, my race packet included three items: my race numbers, a copy of the rules from the event website, and a stack of advertisements about an inch thick.

At the next station, I was provided a timing chip and the coding on it checked to ensure it had my information. We were then directed into the Ironman merchandise section, of course.

We walked back to the hotel (a half-block away) to get my bike on the premise we would check it in at the transition area. Like packet pick-up and the expo, the hours for bike check-in were from 10:00AM to 5:00PM. As we headed out with my bike, we were stopped by another athlete who was returning with his bike and informed us that the transition area would not likely be open for a couple of hours. We decided to instead attend the 11:00AM athlete meeting and drop the bike off afterward.

Given the large international population competing in the Miami event, the athlete meetings needed to be delivered in both English and Spanish. Rather than having separate meetings in the two languages, we sat for an hour while twenty minutes worth of information was disseminated alternating in English and Spanish. It was at this point that we learned many of the rules that had been distributed in the past few days (and even an hour earlier in our race packet) were not actually applicable. For example, there was no changing tent and we had to transition at our bike with our gear. If you packed your gear based on how the race director told you the race would work, this was kind of a pain in the butt. I didn’t bring a towel to lay my gear on at the bike rack (wouldn’t be necessary according to the rules we had been provided) though this was easily solved by “liberating” one from the hotel for the day. I can only imagine that at least some athletes had planned on changing from a swim suit to cycling shorts for the ride; not sure what exactly they ended up doing.

It also became apparent during this meeting that the race officials didn’t truly understand the USAT Competitive Rules. As a USAT Race Official myself, I feel it’s important to point out a few things about officiating staff at WTC/Ironman events:

- Race officials at WTC events are not necessarily USAT Race Officials, as WTC provides its own officials who may or may not be cross-certified,

- WTC events typically request and receive approval for a large number of rules dispensations (fancy word for exceptions) that allow them to add or change rules, or disregard them entirely,

- WTC events often have rules that differ from each other, making it a challenge for both the athletes and the officials enforcing the rules to understand exactly what they should be doing, and

- Aside from rules for which a dispensation has been approved, the USAT Competitive Rules are still the underlying framework for the event rules and there’s no excuse for a WTC race official not understanding them.

Now, with all that said, the head referee for this event began to explain things incorrectly from the start. He started by suggesting that your draft zone is defined as four bike lengths between you and the bike in front of you. First, your draft zone goes backward from the leading edge of your front tire, not forward to the bike in front of you. That’s the draft zone of the rider in front of you, not your draft zone. Second, the draft zone extends back 7 meters (a little shorter than 23 feet) which is less than four typical bikes, so when you include the bike being ridden by the owner of the draft zone, that means there are (at most) three bike lengths between bikes when draft zones are properly observed. This may sound picky (and I’d even argue that it’s not) but when half the athletes are from another country, it is important to properly explain the rules to them if you want them to abide by them, isn’t it?

There were smaller misstatements of the Rules, such as explaining that the wetsuit temperature cutoff was “84-ish”, whatever that means, but one of the most noticeable problems in his discussion on the rules was when he attempted to explained Unauthorized Assistance, which states that an athlete may not accept assistance from anyone other than a race official. While explaining that he doesn’t care if a non-competitive athlete helps another non-competitive athlete who is having a mechanical problem with a bike, he states that since you’re stopped on the side of the road, he’s going to give you both a variable time penalty anyway… WHAT?! Apparently stopping on the side of the road violates some rule that none of us had ever heard of. Nobody asked about it and by the time this had been explained in Spanish, I realized that I didn’t really care anyway.

At the close of the meeting (around 11:50AM) the presenter told us that he was being told that the transition area was now open and we could go check our bikes in, so Jen and I headed back to the hotel so that we could drop my bike off and we could continue on with our plans to visit the Vizcaya Museum for a few hours.

I walked my bike to the transition area two blocks away to find a couple hundred athletes standing in the midday Miami sun and looking really, really happy about it. All of them had been consistently told they would have to wait 10-15 more minutes, and this message had come from the transition director every 30-40 minutes for the past couple of hours.

As more and more athletes arrived, I waited stood around for about an hour and then moved into the nearby park to find some shade where I stood for another half-hour. Jen showed up about the time I relocated to the shade and brought with her a cold Gatorade. The transition folks were nice enough to bring a dozen or so bottles of Ironman Endurance sports drink to the transition entrance for the 300 athletes to fight over.

Eventually the transition area was opened I moved out of my shady spot to make my way to the bike racks. As I went into the transition area, one of the volunteers checking bike numbers rerouted everyone within about a 400-number range to the side (in the sun, again) and told us we had to wait because our bike racks were not ready. After about 15 minutes, they told us they had sectioned off the wrong people, our racks were in fact ready, and we could go to our racks and leave our bikes. The bike numbers were approximately 13″ apart, which hardly leaves room for bikes to be racked properly. On many racks, bikes had to be racked with the from wheel turned 45 degrees for the bikes assigned to the rack to all fit.

We were told several times while waiting that bike check-in would not be extended past 5:00PM despite the late opening, so many of the athletes who were there during their lunch hour waited and waited because they worried they wouldn’t make it back at the end of the workday in time to drop their bike. We came back to look at the transition area a few minutes before 5:00 to learn that bike check-in was now running until 8:00PM.

Swim entrance at Ironman 70.3 Miami

Through discussions the following morning and written comments later by other athletes, I’ve learned that our bikes were left in the transition area with a single security guard walking around in the general proximity. It’s worth noting that there was no place outside the transition area where all of the bikes could be seen simultaneously. Several athletes came by on their way back to their hotels and mentioned that they saw nobody near the transition area. One athlete was with a friend who reached over the soft fencing and picked a competitor’s race bike to see how heavy it was. Nobody challenged the athlete or, to the best of their knowledge, even saw that this occurred. Indeed there was a Scott triathlon bike missing the following morning and after numerous announcements asking athletes to look around their racks for it, a competitor with no bike was forced to withdraw before the race even started.

A number of bikes were leaned against the fencing during bike check-in as there were not bikes marked for numbers within their range. These bikes had been moved to a rack by the following morning, and it was one of the bikes in this group that went missing.

Pre-Race

On race day morning, I woke at 4:00AM to eat and get ready for the event. All of my gear was packed from the previous night and I was pretty amazed that I was able to fall asleep with no problem the evening before. Having eight hours of sleep feels so much better than trying to race on only two or three hours. I had a bagel with peanut butter and got dressed, sipping on a bottle of Gatorade as the time passed. Around 5:00AM, I headed out to make my way two blocks to the transition area.

Body marking stations were set up outside transition and there were adequate and friendly volunteers. This is a good place to have friendly people since it’s most often the first contact you have with a race volunteer. The kid marking me made small talk and wished me luck and I made my way to my bike.

While I was entering transition, I overheard the announcing telling us that the race course was not ready, it was almost certain that we would be starting late, and that he would let us know shortly how late. I tried to feel surprised about this but was unable to do so.

I checked the air in my tires and set up my transition gear, including overlaying my run gear with a plastic bag in case the rain in the forecast was enough to soak my shoes while I was out on the bike. It sprinkled for a few minute at one point but that was the only precipitation we saw.

As the time to swim began to arrive, the transition area was closed and athletes made their way toward the swim start. The delay of the race start was between 10 and 15 minutes.

Waiting to start the swim at Ironman 70.3 Miami

Swim

The swim portion of the event takes place in Biscayne Bay and consists of a 1.2-mile loop into the Bay and then around the buoys back to Bayfront Park where you swim parallel to the park and exit onto a wooden dock stairway close to the entry point.

Ironman Miami 70.3 Swim Course

The entry point is from a wooden and cement dock behind Bayside Marketplace which is approximately 5′ in width. The athletes do not enter the water as a group from the side of the dock but two-by-two off the end of it. Some of the waves contained 200-250 athletes and the waves were 4:00 apart with about a 40-yard swim from the dock to the start line buoy. You do the math. Getting 250 athletes into the water in 240 seconds means that one goes every second, and even at that rate, a fair number of them will not even be at the start line when the wave starts.

There were two volunteers stationed at the end of the dock whose sole responsibilities were to push athletes off the dock and into the water in quick succession. I understand the necessity to move athletes quickly into the starting area, but pushing athletes unexpectedly into water is never acceptable, and there was no time given to the athlete ahead of you to clear the water or in most cases, even surface completely. I was pushed into the water with little clearance from the cement dock and into an area of water that still had an athlete submerged in it. Before I could surface, the athlete behind me landed in the small of my back.

Getting pushed into the swim start area.

For many of the waves, the field was not entirely in the water when the wave started, meaning athletes were still lined up on the dock making their way into the water and their swim time was already ticking. For each of the waves where athletes were still on the dock, there were also athletes who had swum beyond the start buoy and were already into the course when their wave swim started.

Rounding the first buoy of the swim.

Once in the water, we realized that it was impossible to sight the course as only four buoys had been placed in the Bay (those at each of the four turning points) and it was not possible to see across the length of the second, third or fourth lengths of the course. Adding to this challenge, the earlier waves started before sunrise when it was still dark, and the later waves were swimming into the rising sun. In response, the lifeguards on their surfboards (and tired of being asked the way to the next buoys) sat pointing at the next buoy so that athletes could tell which way to go. While this is helpful to the athlete that is swimming, a preoccupied lifeguard is not particularly helpful to an athlete that for some reason is no longer swimming.

I expected to swim about a 2:30 pace (per 100 meters) and though I felt like I had a strong swim, my chip time was 58:04, which translates to approximately a 3:03 pace. A number of athletes have suggested that this course was in fact about 2,400 meters in length (as opposed to the expected 1,900 meters) which would mean my swim pace was around 2:25. Based on this (and this alone) I see sufficient reason to support that the course may have been long, though I have no way of estimating how long.

The exit from the swim was onto a wooden stairway that had a rail on each side and was extremely slippery. Volunteers were in place to instruct us not to climb the stairs unless we were holding onto the rail, which means only two athletes can emerge at the same time. This wasn’t a problem for me since I’m not usually in a competitive pack of swimmers, but I understand there were several “fights” for the stairwell in the faster groups.

Transition 1: Swim to Bike

My transition from swim to bike is something I had hoped to improve upon and was able to do so with a 4:32 T1 time. There were no problems with the transition and, as usual, I had plenty of room to work since all the faster folks were long gone.

Running into T1 from the swim.

Bike

The bike course requires getting out of the downtown area from transition, and as such includes roads that are perhaps not in the best of conditions. One would think this should be a factor when identifying potential venues for triathlons. The street conditions during the first couple of miles included a massive number of potholes, bumps, road cracks, etc.

In the past 18 months, I’ve cycled more than 4,500 miles and have lost a water bottle once, during a Sprint distance race on a road that had a huge pothole, which also happened to also bounce everything out of my Bento box as I discovered it during a pass and too late to avoid it.

I lost my water bottles four times in the first two miles of Ironman 70.3 Miami. The first time was my Perpetuem nutrition bottle so I had no choice but to go back for it. As I ran up to it, I watched a police officer kick it across to the other side of the roadway, only then realizing that he and his partner were trying to kick them hard enough to burst them open. Yes, because that’s really funny. I made a comment that they were being stupid, he made a comment that I was the only athlete to come back for my bottle, and I headed off quickly before I got myself in actual trouble, placing the bottle in my frame cage instead of the one behind my seat.

I lost my other bottle (which only contained water) three times, prompting me to eventually shove it into the pocket of my triathlon jersey. I was doubtful about whether it made sense to go back for a bottle with only water in it, but the USAT Official in me has trouble leaving anything out on the course, and I would be thankful later that I did retrieve it.

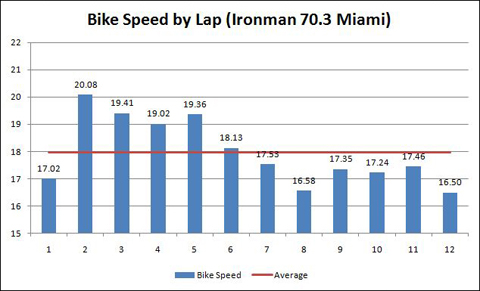

During this first five-mile lap on the bike, my average speed was only 17.02 miles per hour (as opposed to in the mid-19s or low 20s for the next several laps) which highlights not just the amount of time wasted as a result of having my bottles ejected from their cages, but the amount of energy expended to stop and get back up to speed several times. Anywhere along the course that a significant hole or large bump in the road was found, 50-60 water bottles were within 20′ of the obstruction.

Once out of the downtown area, the bike course seemed fairly nice, though there was an excessive amount of 90-degree turns that required athletes to turn and accelerate an unusually high number of times. The course basically zigzagged through the suburbs of Miami.

The bike course was supposed to have three water stops, at miles 15, 30 and 45. We learned in the athlete meetings that these aid stations would each have bottled water, bottled Ironman Endurance sports drink, PowerBar gels, bananas, bagels, and fruit. It was reiterated to us several times that we needed to throw down a water bottle before the aid station and pick up a replacement as we went through.

In actuality, the first two aid stations had no nutrition and the third one had some PowerBar gels. As for hydration, the first station was handing out bottles of water or Ironman Endurance, and I took the latter. It was still sealed and quite slippery, so I rode in aero using both hands to try to open it.

By this point, I was starting to see well-formed lines of athletes that numbered 60-75 in strength. While there were certainly packs of 20 or 30 that were just bunched up, there were as many well-formed, wheel-to-wheel, actual pace lines. If you figured 60 athletes and four or five pace lines, that’s a fair percentage of athletes cheating. What I didn’t see frequently, was race officials. On the rare occasion that I saw an official, he was usually following some solo rider who was struggling along and staring at him as though he would eventually discover a violation.

Drafting on the bike course at Ironman 70.3 Miami.

I did notice that illegal position and blocking violations were significantly more prevalent that I’ve seen in past races (both as an athlete and as an official) and to some extent, I attribute this to the number of foreign athletes and their lack of understanding of the rules under USAT. I heard several people suggest that South Americans drive on the left side of the road, and the rules on the event website do append their explanation of the illegal position rule with “Since in the USA we usually ride on the right and pass on the left,” but after checking four countries in South America, Mexico, and Cuba, I’ve discarded this idea as they all drive on the right. It’s also possible that many of the athletes just don’t care about the rules, as I would see on the run course, but I have trouble believing that riding to the left creates sufficient convenience for the athlete that they would do it just out of disregard.

Around halfway through the bike course was when the wind picked up. I had expected wind of 10-20 mph based on the weather forecast, according to weather service data for that area at that time of day, the sustained wind speed was 18 mph and gusts were at 27 mph. The turnaround point was a three-mile straightaway head-on into the wind on a road that leads to a landfill. In other words, while you’re sucking air, it’s nasty air. The ride back out, though accompanied by a tailwind wasn’t much better and still smelled horrible.

The second aid station had neither hydration nor nutrition and the volunteers had actually moved away from their tables so that athletes wouldn’t think they had supplies and slow down unnecessarily. By this point, I had learned that Ironman Endurance, while fine by itself, when consumed on top of Perpetuem makes me sick. I had a little bit of my Perpetuem left and a few sips of water from my second bottle, so I continued on. Athletes were reportedly seen consolidating water from discarded bottles near this station. There was also supposed to be a penalty tent at this stop, but there was not one.

To be honest, by this point, I really didn’t care about my time anymore. I had slowed down after the confusion of not knowing where the second aid station was and my average speed had dropped from 19 or 20 mph in the first half of the bike course to 17 or 18 after the wind had picked up. As I knew coming into the race, my swim would be slow and my run would be a challenge, so I saw little reason to push hard on the bike, and the circumstances of the event so far simply made it easier for me to let off.

Lap splits during the bike course.

With the wind picked up now, it was good to get back into the neighborhoods where the houses added at least some level of barrier to the winds. I was riding on new Bontrager 50mm aero wheels and to some extent, I’m still getting used to the squirrelly feel of the bike in a good crosswind, but I didn’t experience any problems during the race.

By this point, I was literally yelling at athletes who were riding to the left of their lane to move over. I realize they don’t understand “on your left” and I had grown tired of slowing await their movement out of the way. That takes a lot of energy across a span of 56 miles.

One positive thing to recognize about this event is the way in which local law enforcement managed the bike course. I felt horrible for the people of Miami, where traffic is always significant, and who sat for hours on roads where perhaps one or two cars were able to get through every few minutes. The police officers at intersections along the course were professional and courteous, even friendly, and they did a spectacular job.

On the approach to the third and final water stop, I could see volunteers in the roadway, so like the other athletes around me, I offloaded the empty bottles in my cages and slowed slightly to grab a fresh bottle of water. Also like the other athletes around me, I screeched to a stop just past the water stop to go back because they weren’t actually handing out anything. They had five-gallon jugs of water, but not bottles. There was also no Ironman Endurance (which was fine by me at this point) and as mentioned earlier, the only nutrition they had was a few gels. Some of the athletes went back to where they had discarded bottles and grabbed one (no idea whose) to fill with water. Other athletes simply drank from the jugs and moved on. I filled my mostly-empty water bottle and headed out to finish the bike course.

Coming in off the bike to T2.

Transition 2: Bike to Run

My transition from bike to run was slower than I wanted because I took time to grab a few energy gels from my bag (which I didn’t expect to have to do) and put on sun block. A number of athletes complained that there was no water, ice, Ironman Endurance or nutrition at the water stop coming out of T2 but I was able to get a cup of water that was a little warm but not too bad.

Taking a break to say ‘hi’ to the wife during the run course.

Run

I’m going to start by saying the air temperature for Downtown Miami on this date was 87F and the humidity was 82%, which yields a heat index of 104F. Given that the course had only about 400′ of shaded area (in the shadow of a building and only very late in the race) and another 200′ where it passed under the causeway bridge on the east end, there should have been both ice and sponges available on the course though neither were. In fact, a couple of the aid stations never had ice, and a one had two volunteers (who kept refilling coolers) and no cups. This means that sweaty, salty, disgusting hands/wrists went into the drink to scoop out cupfuls.

There was no nutrition on the run course. None. No gels, no bananas, no bagels, nothing. All of this was promised by Ironman and reiterated as being available through race information on the website and by race officials in the athlete meetings. To be fair, two of the aid stations did have Coca Cola, though one just had cans of it sitting in the sun so it was not only hot, but carbonated. This causes obvious problems for the people behind you.

Cheating on the run course was rampant, particularly with South American teams. Pacers on both bike and on foot were a common sight, and these groups had people openly changing out Fuel Belt bottles and providing ice or cold drinks. This creates an unfair advantage in any triathlon, but especially so in the conditions of this particular event.

I had originally planned to run intervals with 4:00 runs at a 9:35 pace target with 1:00 recovery walks. This plan never really materialized, perhaps because I was behind on my nutrition expectations, perhaps just because of my attitude at this point. I instead jogged down the bridge on all eight passes, walking the rest of the course.

On the run course of Ironman 70.3 Miami.

During my first of two loops of the course, I was on track for a three-hour half-marathon, though I ended up finishing in 3:10. I attribute this to having to stop longer at aid stations to get my own drink, etc.

Coming into the Finish Line at Ironman 70.3 Miami.

Post-Race

Crossing through the Finish Line was not exciting in the I-just-did-a-half Ironman kind of way, but more so in the thank-God-this-mess-is-over way. After coming through and letting them take my chip, I was given a medal and pointed to the shirts. At the shirt table, I was told that all the Large shirts were out, but more were on the way and it would be 10-15 minutes. I was told that I could just come back and get one if I wanted. After confirming with other volunteers that I wouldn’t be allowed back into the Finish area, I ruled this option out and waited, along with 15-20 other athletes, despite there being no shade or place to sit.

After about 45 minutes, I told the Finish Area Director that I couldn’t stand here any longer, that coming back later for a shirt was not an acceptable option, and that we needed to go to where the Large shirts were and get me one. He and I walked the 150′ or so (makes you wonder what happened to the guy who left 45 minutes ago to get them, huh?) and discovered that there are no more Large shirts. So, I had to settle for a Medium shirt, which he gave me along with a Finisher towel. Maybe I’m a shirt snob, but based on my experience with Ironman and for $275 entry fee, I would expect a technical shirt. I received the thinnest, cheapest cotton shirt I’ve ever seen, which was made in Laos. The total time from when I crossed the Finish Line to when I exited the Finish chute with my shirt was 55 minutes.

Later that evening while having a drink in Bayside Marketplace, my wife and I observed a guy still wearing his bright orange volunteer shirt, carrying a black garbage bag stuffed full of race material, and handing out Finisher towels and shirts to employees in the various shops. And I thought my Ironman 70.3 Miami swag couldn’t possibly feel less special.

The post-race area had Cuban food (rice/chicken) available which is probably understandable given the demographics of the athlete field, but there wasn’t anything else. Apparently there was pizza that had already run out. Many of the food vendor stations were empty and a couple others were nearly finished packing. The food area was comprised of numerous tables and few chairs, though the tables were all covered with garbage and half-eaten plates of food. Several trash cans sat empty around the perimeter of the post-race area. Athletes are to blame for not throwing away their food, but Ironman is to blame for not having at least a couple volunteers to throw away trash.

Race results are unavailable as the event website (http://ironmanmiami.com) has been taken down and Ironman.com is not providing any further information. Individual results could still be retrieved through Athlete Tracker for a couple of days, but assessment of penalties (or the lack thereof) cannot be reviewed.

Athlete’s area of Ironman 70.3 Miami. Disgusting!

Final Results

1.2-mile Swim: 58:54

T1 (Swim to Bike): 4:32

56-mile Bike: 3:11:27 (17.55 mph)

T2 (Bike to Run): 6:17

13.1-mile Run: 3:10:10 (14:30/mile)

Total Time: 7:31:20